Show results for

Deals

- 4K Ultra HD Sale

- Action Sale

- Alternative Rock Sale

- Anime sale

- Award Winners Sale

- Bear Family Sale

- Blu ray Sale

- Blues on Sale

- British Sale

- Classical Music Sale

- Comedy Music Sale

- Comedy Sale

- Country Sale

- Criterion Sale

- Electronic Music sale

- Fantasy Film and TV

- Folk Music Sale

- Hard Rock and Metal Sale

- Horror Sci fi Sale

- Jazz Sale

- Kids and Family Music sale

- Kids and Family Sale

- Metal Sale

- Music Video Sale

- Musicals on Sale

- Mystery Sale

- Naxos Label Sale

- Page to Screen Sale

- Paramount Sale

- Pop and Power Pop

- Rap and Hip Hop Sale

- Reggae Sale

- Rock and Pop Sale

- Rock Legends

- Soul Music Sale

- TV Sale

- TV Sale

- Vinyl on Sale

- War Films and Westerns on Sale

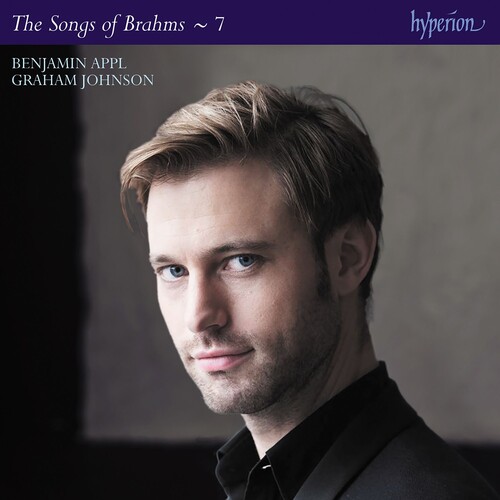

Brahms: The Complete Songs 7

- Format: CD

- Release Date: 3/30/2018

Brahms: The Complete Songs 7

- Format: CD

- Release Date: 3/30/2018

- Label: Hyperion

- UPC: 034571131276

- Item #: 2014924X

- Genre: Classical

- Release Date: 3/30/2018

Product Notes

This is the seventh volume of a series of ten that will present the entire piano-accompanied songs and vocal works of Johannes Brahms. As such it is a companion to the series undertaken by Hyperion for the songs of Schubert, Schumann, Fauré and Strauss.

Brahms issued the majority of his songs in groups collected by opus number. There is a tendency in modern scholarship to suggest that he envisaged performances of his songs in these original opus number groupings. Of course one cannot deny that some planning (though of a rather variable kind) went into the arrangement of these ‘song bouquets’ (the composer’s own expression) for publication, but good order and cohesion in printed form (as in an anthology where poems are arranged to be discovered by the reader in a certain sequence), though pleasing to the intellect, do not automatically transfer to the world of the recital platform where one encounters a host of different practical problems, casting (male or female singer) and key-sequences (high or low voice) among them.

Printed poetry collections are as lovingly assembled as an opus of a composer’s varied settings, but this does not mean the poems therein are designed to be read aloud from cover to cover: the compiler of these volumes, whether or not the poet himself, would expect items to be selected by the reader according to taste or need. The anthology (or indeed opus number) might be likened to a well-ordered jewel case from which precious items may be extracted for use, depending on the occasion: the wearing in public of every item therein on a single occasion would be both impractical and vulgar. There is little evidence, especially from concert practice of the time (where items from the Schubert and Schumann cycles were often ruthlessly excerpted), that Brahms’ publications were conceived within a spirit of cyclic unity that called for an integral performance of the entire group.

Each volume of the Hyperion edition takes a journey through Brahms’ career. The songs are not quite sung in chronological order (Brahms had a way of including earlier songs in later opus numbers) but they do appear here more or less in the order that the songs were presented to the world. Each recital represents a different journey through the repertoire (and thus through Brahms’ life). In a number of these Hyperion recitals an opus number is presented in its entirety. In the case of this disc there is no such complete presentation, although the four relatively seldom sung songs of Op 63 to the poetry of Max von Schenkendorf make up a group that might easily have been published in one opus without the two Felix Schumann and three Klaus Groth settings that are added on to them. Apart from this there are four settings of traditional or folksong texts, two settings each of Hoffman von Fallersleben, Daumer and Kopisch, and one each of Fleming, Goethe, Reinhold, Schack and Lemcke whose names are represented elsewhere in the Brahms song catalogue. There are a few poets whom Brahms set only once, and Alfred von Meissner’s Nachwirkung is the only song to words by that poet.

Far from dreaming of complete evenings of his songs in public performance, Brahms preferred to hear no more than three of his own songs in any one concert. This astonishing information comes from an invaluable book of essays—K Hamilton & N Loges, eds.: Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall: Between Private and Public Performance (Cambridge: CUP, 2014). The conventions of music in the home, where so many songs were first heard and discussed in an environment of lively and cultivated enthusiasm, did not include listeners buckling down in respectful silence to a substantial sequence of songs, as if they were at a public concert. Brahms seems to have been happiest hearing his songs as Hausmusik and surrounded by supportive informality—and I daresay Schubert would have said the same about the Schubertiads. The present-day enthusiasm for hidden, implicit, unknown or concealed connections between songs seeks to feed the appetite for a cycle-hungry recital format favoured in the twenty-first century, but almost unknown in the nineteenth.