Show results for

Deals

- 4K Ultra HD Sale

- Action Sale

- Alternative Rock Sale

- Anime sale

- Award Winners Sale

- Bear Family Sale

- Blu ray Sale

- Blues on Sale

- British Sale

- Classical Music Sale

- Comedy Music Sale

- Comedy Sale

- Country Sale

- Criterion Sale

- Electronic Music sale

- Fantasy Film and TV

- Folk Music Sale

- Hard Rock and Metal Sale

- Horror Sci fi Sale

- Jazz Sale

- Kids and Family Music sale

- Kids and Family Sale

- Metal Sale

- Music Video Sale

- Musicals on Sale

- Mystery Sale

- Naxos Label Sale

- Page to Screen Sale

- Paramount Sale

- Pop and Power Pop

- Rap and Hip Hop Sale

- Reggae Sale

- Rock and Pop Sale

- Rock Legends

- Soul Music Sale

- TV Sale

- TV Sale

- Vinyl on Sale

- War Films and Westerns on Sale

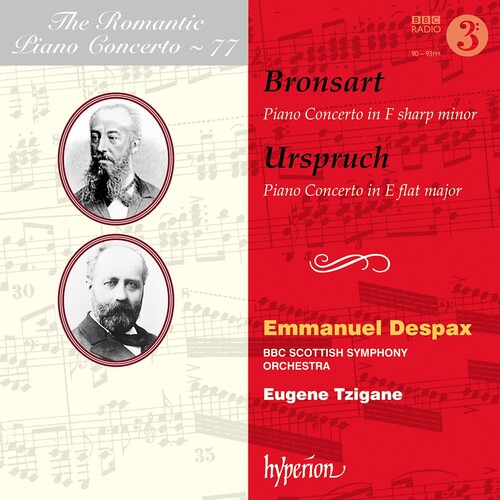

Romantic Piano Concerto 77

- Format: CD

- Release Date: 9/28/2018

Romantic Piano Concerto 77

- Format: CD

- Release Date: 9/28/2018

- Orchestras: BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

- Label: Hyperion

- UPC: 034571282299

- Item #: 2086330X

- Genre: Classical

- Release Date: 9/28/2018

Product Notes

Bronsart & Urspruch: Piano Concertos

Hans August Alexander Bronsart von Schellendorf (generally known as Hans von Bronsart), once a force to be reckoned with in the musical life of his native Germany, is now hardly a footnote in most reference books. Record collectors of a certain vintage will have bought Michael Ponti playing the same F sharp minor concerto presented here, a recording made back in 1973 for the Vox Candide label with the Westphalian Symphony Orchestra under Richard Kapp, one of very few recordings of any of Bronsart’s work. Otherwise, it is probably only keen Lisztians who will know that having revised his piano concerto No 2 in 1856, Liszt chose Bronsart to give the premiere (Weimar, 7 January 1857) with himself as conductor. When the final version was published in 1863, Bronsart was the dedicatee. These were significant gestures. Immediately, one is intrigued. Who was this Bronsart of whom Liszt thought so highly?

He was born in Berlin on 11 February 1830 into an old aristocratic Prussian military family. His father held the rank of Lieutenant-General. Several other relatives held important posts in the military: his younger brothers Paul (1832-1891) and Walther (1833-1914) became respectively Minister of War and Adjutant General to the Kaiser. The family moved to Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) when Hans was still a child, and here at the age of eight he began piano studies. Three years later, we are told, he was playing Schubert-Liszt song transcriptions. After school in Danzig, he entered Berlin University to read philosophy, at the same time studying piano with Theodor Kullak and taking harmony and counterpoint lessons from Siegfried Dehn at the Berliner Musikschule. In 1853 he moved to Weimar to study with Liszt for four years.

Following this, he seems to have had some success as a pianist, touring throughout Europe and travelling as far as St Petersburg, but already his work as a composer was taking precedence. An appearance in Leipzig led to his being appointed conductor of that city’s Euterpe concerts in 1860. The following year he married his second wife, the Swedish-German pianist Ingeborg Starck (1840-1913), a pupil of both Henselt and Liszt, whom Bronsart had first met in Weimar (Wagner, in his autobiography, makes mention of Ingeborg’s good looks). She was a successful composer of operas, songs, marches (her Kaiser-Wilhelm-Marsch of 1871 was a particular favourite) and of a piano concerto written in the same key as Henselt’s celebrated Op 16.

It may be that Bronsart’s name is not more widely known today because of his subsequent career not as a touring piano virtuoso but as a relatively parochial conductor and administrator. After Leipzig, in 1865 he succeeded his friend Hans von Bülow as conductor of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde concerts in Berlin. (A mark of Liszt’s affection for his two erstwhile pupils was that he nicknamed Bülow and Bronsart as ‘Hans I’ and ‘Hans II’.) Two years later he accepted an appointment as Intendant of the Royal Theatre in Hanover. Here he remained until 1887, the year after Liszt’s death, when he became Intendant at the Court Theatre in Weimar, a post he relinquished on his retirement in 1895. He spent the last years of his life in Rottach-Egern, Pertisau and Munich. He died in Munich, just five months after his wife, on 3 November 1913.

Bronsart’s piano trio in G minor, Op 1 (1856), was an early success and his Frühlings-Fantasie for orchestra was praised by Liszt (‘beautiful and invaluable’) but it was his F sharp minor concerto published in 1873 that remained longest in the repertoire. Sgambati and Bülow were among its many champions. Bülow, for instance, gave at least ten performances between 1870 and 1883. In February 1873, one such in Leipzig elicited the opinion from a local critic that ‘only a pianist of Herr von Bülow’s calibre could bring off this, admittedly substantial and not uninteresting, though certainly somewhat uneven, work’. Another, given on 7 December 1877 in Manchester, England, was with Charles Hallé conducting his eponymous orchestra who, wrote the waspish and hypercritical Bülow, ‘accompanied so beautifully, with such confidence, discretion and sensitivity that my tiny instrument was never, not even for a single moment, overwhelmed. I seldom have the fortune to play under such a masterly conductor’.

The concerto opens allegro maestoso, with declamatory dotted statements from the orchestra and then soloist. Brass fanfares and triplet octaves from the piano rising to fff quickly give way to the more lyrical second subject which, after a passage that might have been lifted from one of Chopin’s concertos, in turn yields to a third (and even more expressive) subject. These four ideas are developed and adapted throughout the movement, moving from the tonic to A minor, thence to a section in E flat minor and finally the tonic major, ending in a blaze of triumphant passion, its final measure using the same dotted quaver-semiquaver-quaver motif with which it began.

The lovely slow movement (adagio ma non troppo) is in 3/4 time and the key of D flat major. Muted strings introduce the piano (dolce espressivo) and its graceful melody. A gentle, highly chromatic passage (ppp) takes the music into E major and thence to B major, till its pppp conclusion marked ‘smorzando’ (‘gradually dying away’).

Undoubtedly the most striking movement is the finale (allegro con fuoco). After what has gone before, it would be difficult to anticipate a fiery tarantella movement in 6/8, with the piano setting out the material in forty-two (virtually solo) boisterous bars. The orchestra follows suit, but then at 1'38 the high spirits are interrupted by a stentorian tutti fanfare calling everyone to order. The piano responds insolently with a slightly subdued continuation of the tarantella (giocoso) very much in the vein of Litolff’s famous scherzo from his Concerto symphonique No 4. At the orchestra’s insistence, the piano plays the fanfare theme, a gesture which mollifies the orchestra, prompting them both to join hands in an exuberant return to the opening subject.

Bronsart wrote the concerto for (and dedicated it to) his wife. She must have been quite a pianist. Bülow once described Eugen d’Albert’s piano concerto No 1 as ‘next to Bronsart, certainly the most significant of the so-called Weimar School’. It is difficult to disagree.

If Bronsart’s name and his music are unfamiliar, in comparison to the composer of the companion work on this recording he is a veritable Mozart or Beethoven. ‘Obscure’ hardly covers it. Waldo Selden Pratt’s invaluable New Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians comes to our aid and tells us that Anton Urspruch was born in Frankfurt in 1850, died there in 1907 and that he was an ‘important Hessian pianist and composer’. He became a pupil of Ignaz Lachner (who, with his brother, had been a close friend of Schubert), Martin Wallenstein (a pupil of Dreyschock), Joachim Raff and finally (inevitably?) of Liszt in Weimar. From about 1878 he taught at the new Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt and, after Raff’s death in 1882, at the newly founded Raff Conservatory in the same city. Here he remained until his relatively early death at fifty-six. His wife was Emmy Cranz, daughter of the music publisher August Cranz.

Among Urspruch’s works are a comic opera, Das Unmöglichste von allem after Lope de Vega’s El mayor imposible, choral and chamber works, many piano pieces and songs, an influential book on Gregorian chant (1901)—and the present concerto.

Urspruch’s Op 9 was dedicated to Raff and, not surprisingly, published by Cranz. No fire and brimstone opening for him. Instead we have pianissimo strings playing a lilting 12/8 theme that one feels might at any moment break into Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ symphony. Indeed, throughout its twenty-four minutes, the first movement rarely departs from a bucolic evocation of Alpine meadows and streams. The soloist, though constantly busy, has no bravura role with only a few moments rising above forte. Beethoven is clearly the model for the unexpected and extended cadenza at 19'12. Even here, Urspruch is reluctant to depart from his rural idyll until he abruptly calls a halt to proceedings with two sudden sforzando chords.

The slow movement, marked ‘andante’ and ‘lento e mesto’, is in 2/4 and the relative minor. Muted strings play the main subject, which the soloist decides not to take up, but rather offers a different theme. In fact, it is the woodwind (as solo or ensemble) that are foremost throughout, with the piano in accompanying mode. A brief cadential flourish (marked ‘improvisando’), followed by an unanticipated nine linking bars of fortissimo orchestral tutti (pesante e con forza), lead to a fermata and … the final movement. The solo piano presents a delightful and spirited dance tune which, momentarily, resembles ‘Mein gläubiges Herze’ from Bach’s cantata BWV68. Oboes, clarinets and bassoons then offer a contrasted, more relaxed idea, before the piano enters with a third subject, both strident and Schumannesque. These themes provide Urspruch with the material on which he can play his variations for the remainder of this energetic movement—a fugato at 5'23, for instance; the piano’s moto perpetuo above the strings’ restatement of the initial subject; a tricky version of the same theme (molto più animato) that has the pianist playing different semiquaver passagework in each hand. The music accelerates to the orchestra’s further transformation of the theme in prestissimo triplets, joined ultimately by the piano for the joyful rush to the finishing line.